I've never been plagued by the big existential questions. You know, like What's my purpose? or What does it all mean?

Growing up I was a very science-minded kid — still am — and from an early age I learned to accept the basic meaninglessness of the universe. Science taught me that it's all just atoms and the void, so there can't be any deeper point or purpose to the whole thing; the kind of meaning most people yearn for — Ultimate Meaning — simply doesn't exist.

Nor was I satisfied with the obligatory secular follow-up, that you have to "make your own meaning." I knew what that was: a consolation prize. And since I wasn't a sore loser, I decided I didn't need meaning of either variety, Ultimate or man-made.

In lieu of meaning, I mostly adopted the attitude of Alan Watts. Existence, he says, is fundamentally playful. It's less like a journey, and more like a piece of music or a dance. And the point of dancing isn't to arrive at a particular spot on the floor; the point of dancing is simply to dance. Vonnegut expresses a similar sentiment when he says, "We are here on Earth to fart around."

This may be nihilism, but at least it's good-humored.

Now, to be honest, I'm not sure whether I'm a full-bodied practitioner of Watts's or Vonnegut's brand of nihilism. Deep down, maybe I still yearn for more than dancing and farting. But by accepting nihilism, at least as an intellectual plausibility, I've mostly kept the specter of meaning from haunting me late at night. [1]

Now, if this were the final word on the subject, I'd be perfectly content. Unfortunately, some of my favorite writers of recent years — Sarah Perry and David Chapman, in particular — can't seem to shut up about meaning. Together they've written two books about it, and more blog posts than I care to link to. Even Venkat Rao has dipped his toes in the pool. So I'm forced to accept that either I have bad taste in who I've been reading, or there's more to meaning than I've historically given it credit for.

The way these writers talk about meaning intrigues me. They speak of it as something that can be "experienced," "invested," "manufactured," or "destroyed." I've long struggled to make heads or tails of such metaphors — and yet these are solid, STEM-y thinkers, people I trust not to take me too far off the rails.

What follows is my attempt at figuring out what people mean when they talk about meaning. In particular, I want to rehabilitate the word — to cleanse it of wishy-washy spiritual associations, give it the respectable trappings of materialism, and socialize it back into my worldview. This is a personal project, but I hope some of my readers will find value in it for themselves.

As always, there are caveats. I have a degree in philosophy, but haven't read any of the classic literature on this subject, so I'm almost certainly reinventing the wheel. And although I lean heavily on what I've gleaned from Sarah, David, and Venkat, I'm not sure any of them would endorse what I've written here. You might want to think of it as my own funky synthesis — and if it comes up short, that's entirely my fault.

Now, onward.

Meaning for materialists

How to begin?

Supposing there's no ultimate, objective, metaphysical thing called meaning, we might instead approach it as a certain feeling or perception that people have toward the objects, events, and experiences in their lives, or toward their lives as a whole.

We're all of us, nihilists included, familiar with this feeling. We all know that a wedding, for example, feels more meaningful than a random Wednesday at the office. Or that a letter from an old friend holds more meaning than an electric toothbrush (even though the latter is more useful). We feel meaning when standing in front of a national monument, but not when waiting in line at a grocery store. Music, for reasons I'm only maybe beginning to make sense of, almost always feels meaningful, and probably more so to the average teenager than to the average 50-year-old. (Actually, I suspect teenagers perceive more meaning in almost everything.)

So: meaning isn't a substance, but rather a feeling. In this way, it's a lot like beauty. Both are more-or-less subjective experiences that we perceive in response to external cues. [2] In both cases, people generally agree about which kinds of things elicit the feeling, while at the same time leaving plenty of room for individual and cross-cultural variation. Both meaning and beauty are experiences we seem to crave, and the fact that all humans have these cravings suggests that they're adaptive. And just as we can appreciate beauty without getting too philosophical about it, so too can we appreciate meaning without requiring it to rest on some ultimate, metaphysical foundation.

One especially important feature of meaning is that it's highly contextual. My wedding is meaningful to me, but not so much to you. An inside joke can be meaningful to one community but completely irrelevant to another. Similarly, events in a dream often feel intensely meaningful, but typically lose most of their meaning when we wake up to real life.

In the context of a play, Chekhov's gun is meaningful if and only if it's fired in the final act. If the gun is never fired (or is otherwise irrelevant to the plot), then it's meaningless — not a prop, but mere set dressing. And just as we find narratives unsatisfying when the elements in them don't pay off later, so too do we appreciate when things pay off meaningfully in our lives and the other contexts we care about. Otherwise it's just one damn thing after another.

The meaning of a given thing can also change over time, as David Chapman points out in the case of an extramarital affair. As the affair is taking place, it feels laden with meaning. But years later, long after the two lovers have parted ways, most of the meaning seems to have dissipated. Presumably, if they'd left their spouses and re-married each other, the affair would have retained much of its meaning.

* * * *

Alright, time to shift gears.

So far I've been waving my hands in the general direction of meaning, without trying to put too fine a point on it. Now I'd like to venture a more explicit hypothesis about what, exactly, underlies our perceptions of meaning. Please forgive the mathy tone here:

A thing X will be perceived as meaningful in context C to the extent that it's connected to other meaningful things in C.

Let's take a moment to reflect on this statement and draw a few corollaries.

First, what kind of connections are we talking about? Typically they will be causal: X influences Y. Sometimes they will be epistemic: X justifies or explains Y. But they might also be narrative connections or even mere coincidences. Regardless, the more densely or strongly connected something is to the rest of the meaning "soup," the more meaningful it will be perceived to be.

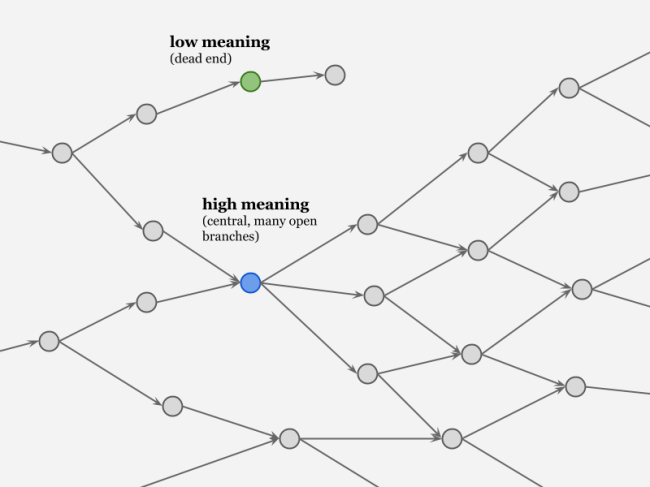

Sarah gives a helpful metaphor: meaning is pointing. So the more arrows issuing out from something, the greater its meaning [3]:

We can also gauge meaning by asking the counterfactual question: "How much of an effect would removing X from C have on the other meaningful things in C?" The greater the effect, the more the meaning.

By these measures — connectedness, pointing intensity, effects of removal — the Constitution is far and away the most meaningful document in the United States. The structure of our government (and many other institutions) owes more to the Constitution than to any other document. If the Constitution never existed, or if it was changed even slightly, the U.S. would be a very different place for all its inhabitants. Similar logic tells us that, in the context of a growing startup, early hires are more meaningful than later hires, largely because they have more influence on how the company develops. Even at the later stages, however, hiring and firing are more meaningful activities than stocking the kitchen or painting the bikeshed.

Second, note the recursion: the meaning of a thing is defined by its connections to other meaningful things. This may seem circular or question-begging, but I think that's precisely the point. Few things are meaningful all by themselves; most derive their meaning from the things they point to. Of course, the buck has to stop somewhere, at some source of inherent or axiomatic meaning. In a religious context, for example, God is the ultimate arbiter of what is or isn't meaningful. Meanwhile, in secular contexts, most people seem happy to accept the premise that human life is inherently meaningful (or something along those lines). Those who insist on pressing further — e.g., by asking why human life is meaningful — must then gaze into the dark abyss.

Third, note that meaning, if defined in terms of connections, isn't entirely a matter of subjective experience. It has some objective qualities, some entanglements with reality. And as such, people can actually be wrong about their feelings of meaning. You might think your job is meaningful, but if a friend disagrees, he probably has an objective basis for doing so. He might tell you, "Actually, your job has no real effect on the outcomes you actually care about." This would be a disagreement about facts, not axiomatic values or subjective feelings.

Finally, if meaning is about connectedness, and especially causal influence, we can see why it's adaptive to pursue meaning. Perceptions of meaning allow us to answer a question we're always asking ourselves, "Why am I bothering to do this?" If an activity feels meaningful, it merits our continued attention and investment. Whereas if it feels meaningless, an appropriate response is to stop doing it — to give up and search for a more meaningful path. To seek meaning, then, helps us avoid dead-ends and retain control over our lives. Just as boredom and ennui are emotions that prompt us to make better use of our time or to look for other opportunities, our perceptions of meaning (or lack thereof) prompt us to think about the deepest, longest-term impact of our actions, and to steer toward better outcomes.

It's important to remember, though, that we can get duped into perceiving meaning where it doesn't actually exist. As in many other areas of life, we can't always pursue the outcomes we want directly. Instead we evolved to pursue a set of cues that give us the subjective sense of meaning. These cues typically correlate with real meaning, but have the potential to lead us astray, and in clever hands can even be used to exploit us. A charismatic CEO, for example, waxing grand and eloquent about the company's mission, can create a strong sense of meaning in his employees — but all too often it's illusory, the reality less "world-changing" than the rhetoric.

Memento mori

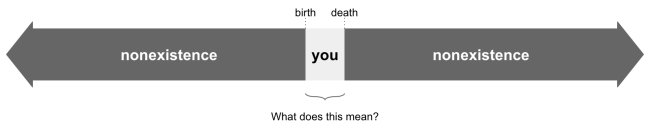

As we all know, the prospect of death throws meaning into high relief. It forces us to consider a broader context in which "we" no longer exist. All those things that were meaningful in the context of our lives will retain little or no meaning once we're gone.

So then, what does matter, as they say, "in the grand scheme of things"?

It might be helpful to think in extremes. The least meaningful life, for example, is the causal dead-end — a person so inessential and irrelevant that the world doesn't so much as bat an eyelash when they die. A hermit who spends his whole life alone in the woods, perhaps. Or someone who toils in utter obscurity, leaving no children and no other mark on the world.

On the other hand, the most meaningful life is the one on which everything depends: the fate of humanity, Good triumphing over Evil, etc. We love hearing stories about characters who experience these epic heights of meaning: Harry Potter, Ender Wiggin, Frodo Baggins. Or consider Jesus's life and his death on the cross, which arguably hits harder on the human "meaning bone" than any other narrative ever constructed. First of all, he saved everyone. Where once there was certain damnation, Jesus gave us a chance at an eternal life in Heaven. Second, his coming was long-prophesied, implying a relevance not just to the future but also the distant past. Finally, he suffered excruciating pain [4] in his dying act, highlighting the difference between a meaningful life and a pleasurable one. (More on this in a moment.)

Now we can't all be Jesus or Harry Potter, of course. But if meaning is pointing, then the meaning of one's life must reside in the arrows that point outward from it, influencing the external world. That's why we so often talk about meaningful activities in generic terms like "connecting with others," "paying it forward," "having an impact," "leaving a legacy," or participating in something "bigger than oneself."

None of this is to say that Alan Watts or Kurt Vonnegut are wrong, or that we must do something meaningful with our lives. But to the extent that our brains were built to seek meaning, we won't be able to quench our thirst by dancing around or making fart apps. So we're left with a choice: either we strive to make a meaningful difference in the world, or else learn to face the void without flinching, and to find peace in simple being. [5]

The experience machine

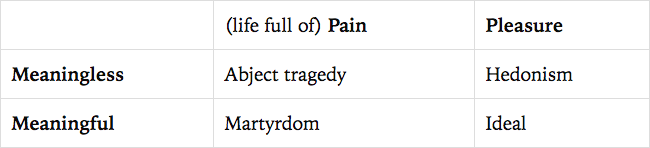

One of the best ways to look at meaning is to contrast it with pleasure. Consider this dramatically oversimplified formula:

Life satisfaction = pleasure + meaning

"Pleasure" here is what hedonists traditionally try to maximize. It includes health, comfort, and all manner of enjoyable sensory, aesthetic, and cognitive experiences, along with the absence of pain, misery, and suffering. Even beauty, for the hedonist, gets rolled up into the pleasure term.

Now we could imagine defining "pleasure" in such a way as to include "meaning." After all, it feels good to experience meaning in one's life. So why break meaning out into its own separate term?

One reason is to highlight how people are often forced to choose between meaning and pleasure; the two experiences seem to trade off against each other in interesting ways. Having children, for example, seems to reduce one's pleasure, at least in the short run, while contributing greatly to one's sense of meaning. (More here.) In the extreme case, martyrs are willing to endure torture and die for the sake of something larger than themselves. And sure, a martyr is a tragic figure — but vastly more tragic is he who suffers and dies for no purpose whatsoever:

But the bigger reason to separate meaning from pleasure is that pleasure is a strictly subjective experience. You can close your eyes and bliss out as hard as you like, and the pleasure you experience will be no less valid because it's "just in your mind." Meaning, on the other hand, is entangled with external reality, making it possible to be wrong about it. And thus the pursuit of true meaning requires an outward orientation to the world.

To drive this point home, consider the "experience machine," a thought experiment originally dreamt up by philosopher Robert Nozick. (Sarah discusses this at length in her book, Every Cradle is a Grave.) The experience machine is a virtual reality life-simulator designed to make you feel happy and fulfilled. A neuroscientist puts you in a tank, hooks your brain up to some electrodes, and starts feeding you wonderful experiences. There are obvious parallels here to the Matrix (although Nozick proposed it some 25 years before the movie). Perhaps the biggest difference, though, apart from the happiness factor, is that the experience machine is designed for a single occupant. It's just you in there, all by yourself. Everyone you interact with "inside" the machine — your friends, family, etc. — will all be simulated.

Now, suppose you're given a choice between (A) continuing life as normal, or (B) plugging yourself into the experience machine. Your choice is completely binding. If you choose the machine, you'll live out the rest of your days in virtual reality rather than base-level reality. It'll be like a perfect dream that you never wake up from.

When confronted with this choice, some people say they'd gladly choose the machine. Many others, however, are put off by the prospect of living in a simulated reality, no matter how utopian. Why?

One reason is that a life in the machine has no meaning, at least from the perspective of someone standing outside it. To choose the tank would be to render your real life a causal dead-end; you'd become as irrelevant as a brain-dead patient on life support. So if you actually care about things in the real world — the lives of your children or other family members, for example — you can't in good conscience abandon them for the machine.

Of course, what you'd experience in the machine might make you feel as meaningful as Jesus or Harry Potter. But at the moment you're presented with the choice, your eyes are wide open, and you know the machine is an illusion. And many people would sooner suffer in reality than live a lie, however beautiful it may be. This is why meaning can't be modeled as simply another piece of the "pleasure" package.

Meaning creation and destruction

Now that we have a tentative grasp on meaning, we can start to reason about different forces in the world and how they act on it. Specifically, some forces create or enhance meaning, while others seem to erode or destroy it.

Children. This is an easy one: children create meaning for their parents because (in most cases) they outlive their parents and become part of their legacy.

Helping others. Another easy one. Every action you take to benefit someone else is an arrow pointing outside yourself and influencing the external world. And because other lives are "inherently" meaningful, you get full meaning-points for helping them.

Community. Consider the difference between a solitary hermit and someone living in a dense, tight-knit community. The hermit has little influence on anything outside himself, while community members abound in connections and relationships — arrows pointing at other meaningful things. All else being equal, then, community creates meaning.

Fame. This one's a bit trickier. It's tempting to say that fame is "empty" or "hollow," and that therefore it doesn't contribute to meaning. Which I suppose is true if we're talking about fame by itself, or fame for its own sake. But I think it's more accurate to say that fame enhances meaning, perhaps by acting as a scaling factor. The more people who watch and listen to you, the greater your influence; every impression is another arrow pointing outward from your life. Now, if your work is meaningless to start with, then multiplying it by fame won't get you any extra meaning. But if your work does influence the world in a meaningful way, then you'll want it to reach as many people as possible. And even if you'll never meet your audience, still you might feel the call to perform, e.g., by publishing anonymously or posthumously.

Network centrality. Joining a community and seeking fame are just two examples of a more general way to maximize meaning: pursuing network centrality. Patrick O'Shaughnessy gives us a dramatic illustration: Why do Americans remember Paul Revere for his famous ride, but not William Dawes for taking a similar ride the very same night? Because Revere already knew people in each of the towns he visited, so when he galloped in with the big news, he only had to tell one person, who then told everyone else in the town. Dawes, meanwhile, just knocked on strangers' doors. Thus Revere's influence spread much farther and wider, and so his ride (and his life) ended up being more meaningful.

Ancestors. Your ancestors — parents, grandparents, and beyond — are meaningful to you in at least two different ways. First, they represent meaning that was spent on you (or, as Venkat says, invested in you); they gave up optionality and made other sacrifices in order to produce you. This creates a kind of debt, but one that mostly has to be paid forward. Second, ancestors bring people together in community. Without your parents' influence, for example, you wouldn't have a relationship with your siblings. Or picture a large extended family gathered around a set of grandparents, the matriarch and patriarch who engendered, both literally and figuratively, such a tight-knit community. Even dead ancestors, especially if they were forceful in life, can create a Schelling point for coordination among their living descendants. This is one reason they're worshipped in many cultures.

Religion. All religions create copious amounts of meaning for their adherents. One way is, again, by fostering community: providing a space and an excuse for congregation, prescribing rituals that get people in sync, and otherwise working to promote network effects. Many religions also advance narratives that give their members a privileged role in the world — God's "chosen people," soldiers in a cosmic battle, etc. These stories may be nonsense, of course, but for true believers, the perception of meaning is real enough, and to lose it or give it up can be extremely difficult. I imagine it's pretty gut-wrenching to trade heaven for oblivion: to recognize that the dead are simply gone, forever, and that we too are destined to die and be forgotten. Is it any wonder why people cling to religion as a source of meaning?

Progress vs. decay. Imagine getting in at the early stages of a venture that promises to be big and important — like a startup company, Genghis Khan's early army, or ISIS in the eyes of its recruits. Expansive open branches, increasing possibilities: it's a heady dose of meaning, right? Economic progress works the same way, although the growth rate is usually small enough that it dilutes the meaning to a less intoxicating dose.

Now imagine being involved in a venture that's rapidly falling apart, like a business on its third round of layoffs, crumbling toward bankruptcy. "Why am I bothering here?" we might ask ourselves. "What's the point?" That's the sickening dread of meaninglessness, helping us steer away from dead-ends (we hope). And again, a shrinking economy produces the same effect, although it plays out more slowly and feels more like a gradual erosion of meaning.

My heart goes out to everyone stuck in a doomed part of the economy. In material terms — i.e., their access to sensory pleasures and creature comforts — their lives rival those of ancient royalty. But cheap goods and indoor plumbing can't make up for the sinking sense that their prospects are dwindling, their communities evaporating, and that their actions and lives are losing meaning day by day.

Space colonization. Perhaps this is a subset of "progress," but it's important enough to deserve its own paragraph. The prospect that humans might someday spread out through the galaxy (and beyond?) creates meaning on an epic scale. It implies that our species isn't doomed to extinction within a single lonely gravity well. There's hope for us yet. And if our future is indeed in the stars, then what we do today, here on earth, will have cosmic consequences. When nerds wax romantic about spaceflight, or about science in general, they're celebrating meaning in their own special way.

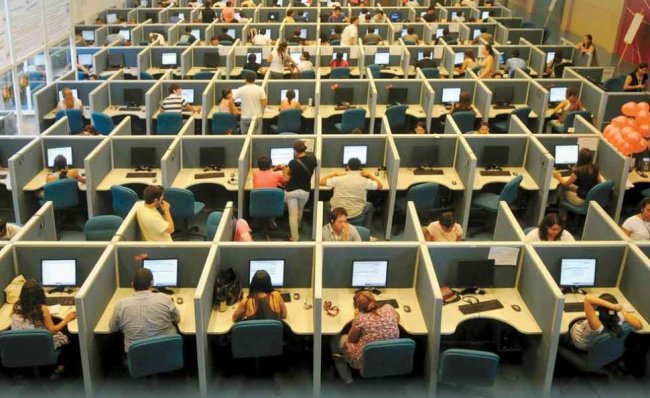

Meaningful careers vs. bullshit jobs. For many of us, a career is a significant source of meaning. Through 80,000 hours of work, we're able to have a non-negligible impact on the world. We might build something of lasting value, help a lot of people, or make a name for ourselves in the history books or textbooks. There's a reason people often put their professions on their tombstones.

Not all jobs are equally fulfilling, however. If your work is low-impact and routinized — i.e., if you're easy to replace — it's only natural to wonder, "What difference would it make if I quit?" In other words, you'll feel a dearth of meaning.

Karl Marx called it alienation, the way the industrial era disconnects its workers from reliable sources of meaning. This happens especially but not exclusively in factories, where workers are disconnected from the final product, from other workers, and from consumers. Even in a white-collar setting, a corporation runs better when its employees are fungible, and thus it's incentivized to push toward becoming a bureaucracy. This contributes to economic efficiency (yay!) and shareholder profit (yay?), but it slowly sucks meaning out of the workplace.

Now factory jobs may be unpleasant, but at least they're fundamentally worthwhile: someone has to work the assembly lines, or the products won't get made. But David Graeber goes further and says many modern jobs are actually bullshit:

Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul.

I'm not sure I agree with everything Graeber says in his essay. But certainly a lot of jobs, firms, and even entire industries are zero-sum in nature (or worse: exploitative), and I can only imagine how demoralizing it would be to sink so much personal effort into them. Of course, workers can always choose to give up some pay for a more meaningful workplace, and many of them do. But our consumerist culture doesn't make that tradeoff easy for people, perhaps to our collective detriment.

Science

Let's end where we began, shall we? — by asking what science has to tell us about the meaning of human life, our significance in the context of the entire universe.

(I don't mean to imply that science has better or more important things to say about meaning than any other discipline. I just happen to be fond of science, so please, humor me.)

As we all know, science tends to undermine traditional sources of meaning. It rejects the notion of a soul that carries on after death. It subverts mythological plot arcs that provide a special role or purpose for our species. It tells us that we were descended not from gods, but from apes (and ultimately from bacteria!), and that we arose simply because we're good replicators; we are, as it's often said, "pond scum" on the surface of an obscure rock. As if that weren't enough, science regrets to inform us that the inevitable fate of the universe is entropic heat death — that we and all our creations will eventually dissipate, like ashes scattering in the wind.

This is none too promising. But what science taketh away, it can also giveth back — kind of.

Yes, science tells us that we're rounding error in terms of size and energy consumption. But in terms of complexity, we're huge. As far as we know, we and our societies take the prize for being the most complex structures the universe has yet evolved. And thanks to our ingenuity, there are more things deserving of study on the surface of one planet (Earth) than in the entire rest of the known universe.

I don't mean to boast, but we're kind of the life of the party here.

And though we're small and powerless now, there's cause for optimism. We may yet colonize Mars, build a Dyson sphere, or spread our wings and populate the galaxy. And if we do, it'll be because we're the only creatures (again, as far as we know) with the ability to accumulate knowledge in a scalable way. We've trained this learning engine — our minds augmented by culture — on everything we can get our hands on: dirt, rocks, flowers, squirrels. Using telescopes, we've trained it on the night sky, and using microscopes, we've trained it on the tiniest bits we're made of. We've even been able to learn things about the distant past and make guesses about the distant future. All our progress, from medical to moral, we owe to this art. And we're currently using it to learn how our own minds work, so that we might build faster, more powerful, and more sensitive minds to extend the reach of our thought.

Alan Watts gives it some poetic oomph, as always:

Through our eyes, the universe is perceiving itself. Through our ears, the universe is listening to its harmonies. We are the witnesses through which the universe becomes conscious of its glory, of its magnificence.

So there is a distinguished place for us in the cosmos. I'm not sure it's worth much in terms of ultimate purpose. But it sure beats the old "pond scum" story, at least in one nihilist's opinion.

_____

Thanks to Jesse Tandler for a good conversation along these lines.

Endnotes

[1] specter of meaning. Then again, I'm only in my 30s. I have a feeling the specter will return with a vengeance in later decades.

[2] subjective experience. Random speculation: meaning is perceived largely by the right hemisphere of the brain.

[3] arrows. One can imagine using graph theory to define meaning in a rigorous way. Anyone care to take a stab?

[4] excruciating. Note from the Etymology Fairy: ex- + crux, from the cross.

[5] striving vs. being. Other options include palliation (drugs, TV, video games) and self-deception — both very popular.

Melting Asphalt

Melting Asphalt