I hate the nature vs. nurture debate. It's a seductive but very dangerous formulation. As a rule of thumb, whenever a discussion of personality gets framed in terms of 'nature' and 'nurture', everyone loses 15 IQ points up front. Your best bet is to run for the hills.

The reason it's dangerous is that it sets up a false dichotomy. Nature versus nurture. Who you are (it's assumed) has to come from one or the other of those two factors. To say that it's a mixture or interaction between the two is only slightly more sophisticated.

As I'm going to argue today, 'nature' and 'nurture' aren't the right basis vectors for analyzing personality. Nature doesn't trade off against nurture in determining who we become. Instead it goes something like this:

Nature and nurture work together to create a prototype, which then negotiates with the external world. The result is a strategy for getting along and getting ahead — a strategy we call "personality."

If you didn't catch all of that, don't worry. I'll step back and explain.

The what, the why, and the how

To understand a complex mechanism like personality, you need to answer three questions: What is it? Why does it exist? And how does it work?

It's important to ask those questions in the right order. Specifically, why needs to come before how. In order to understand how personality develops, we first need to understand its purpose — what it's developing towards. Nothing about the mechanics of personality will make sense except in light of its purpose.

And once we understand the why and how, the what will fall out quite naturally. In the meantime, a layman's understanding should suffice to get us started. Or if you want something more canonical, here's my high school psych textbook (Myers 1995):

Personality is a person's characteristic way of thinking, feeling, and acting.

As definitions go, this is great — but it's purely descriptive. So let's turn our attention instead to personality's role and purpose.

Adaptive brain design

Here's a thought experiment (slash design exercise):

Imagine that you're the set of genes charged with constructing a human brain. It's your responsibility to decide how the brain will be configured and how it should behave. Anything that's biologically possible for you to build into the brain, you can decide to build. But you have to do all your work 'up front', before the brain (and its body) leave the womb. After that, it's hands off. So you better make sure your design can handle all the possible situations it might confront during the course of its life.

Since this is a design exercise, you might find it useful to think about all the functions your brain will need to perform, and to separate them into (a) functions that should come pre-wired, vs. (b) functions that can (or should) be learned later, in response to what the brain encounters in the world.

Some functions should definitely come pre-wired, so your brain (and its body) can hit the ground running, so to speak. These are things like: a desire for food, water, and sex; an affinity for early caregivers; a sense of curiosity (to motivate exploration); a healthy fear of loud noises; etc. These will be useful in almost any environment, so you might as well build them in up-front, to avoid the costs of learning by trial-and-error.

But the space of all possible environments is vast and varied, so only a small fraction of behavior patterns can be fixed up front; the rest need to be contingent on different features of the environment. For example, if you're building a female brain, you should program it to seek sex more readily when resources are plentiful, but to abstain when resources are scarce. This is because pregnancy is relatively safe during 'good times' (when there's easy access to food, water, and physical protection), but much riskier during tough times, when having an extra mouth to feed might mean that both mother and baby will starve.

Of course the "environment" here isn't just the physical environment (landscape, weather, predators, prey, parasites, etc.). It also includes the other humans in your tribe and the culture they've been growing over the years — the social environment, in other words. So your brain is going to need to pick up on a lot of social cues and modify its behavior accordingly.

But there's another, even more important reality that your brain has to confront and adapt itself to: its own body.

If this sounds counter-intuitive, it's because we usually think of the brain and the body as being 'on the same side', united in confronting the external world. And it's true that, from the perspective of the genes, the brain and the body are on the same team. They're both built in order to serve those genes — to maximize genetic propagation. But from the perspective of the brain, the body is just another unknown — another external variable it needs to account for.

Remember, in this design exercise you're not representing the entire genome — just the subset tasked with designing the brain. You don't know what other genes you're going to be paired with. You have to be prepared to get shuffled into genomes that produce all different types of bodies — big and small, strong and weak, beautiful and ugly, skilled and clumsy. The brain that you build has to be ready to produce behavior tailored to any of these different body types.

If (for example) your brain ends up with a weak, sickly, or otherwise feeble body, it should (all else being equal) respond by developing a meek personality. To do otherwise would be dangerous. If a feeble-bodied brain stubbornly insists on having an adventurous spirit, it's liable to end up in the jaws of a tiger or drowned in a river. Or if it insists on an aggressive interpersonal style, it's liable to end up beaten or dead at the hands of a rival.

So your brain is going to have to learn, on the fly, what kind of body it has — what its strengths and weaknesses are, how it compares to the bodies of its peers, etc. This is important both for surviving physically and for competing socially.

But what if you knew, in advance, that you (the brain-genes) were going to be paired with the genes for a specific type of body? For example, maybe you know you'll be paired with genes for a highly symmetrical face, or those for a huge, hulking body. Does this change which behavior patterns you can pre-wire, vs. which need to be learned later?

Unfortunately, no. Even if you knew the entire genome you're going to be paired with, it still isn't safe to tailor your brain to the given body-plan. The problem is that there's too much variance in the development process. How your body turns out isn't fully determined by its genes, but rather emerges from the interaction between genes and environment. You might, for example, have the genes for a beautiful face, only to find your face marred by disease in early childhood. Or you might have genes that would normally produce a hulking body, only to find yourself malnourished and therefore stunted.

But it's even worse than that. It's not just noise in the development process that you can't predict — you also can't predict who you'll end up living with. You might have the genes for a hulking body, only to find that everyone in your tribe has an even hulkier body.

This is a heavy dose of relativism to absorb. The reality is that there is no objective reality, at least when it comes to who you are. Everything about yourself that you might care about only makes sense relative to the other features of the environment.

From the brain's perspective, its body and its environment are but two sides of the same coin. All that matters is how the body fits with its environment. The brain can't distinguish between (on the one hand) having a strong body among weak peers, weak predators, and weak prey, and (on the other hand) having a weak body among even weaker peers, predators, and prey. "Strong" and "weak" have literally no meaning without reference to the environment.

But it's OK. We don't need to predict how things will turn out. We just need to wait and see — and then adapt ourselves to what we find.

Making lemonade

The brain design exercise (above) suggests that the reason we develop a unique "personality" is to adapt to the specific (but unforeseeable) circumstances our brains end up confronting. In other words,

Personality is a strategy for making the most of one's particular lot in life.

Fate deals you a random hand of cards, and it's your brain's job to assemble a strategy that gives you the best possible chance at winning.

Life hands you lemons? Make lemonade. Life hands you a feeble body? Start by acting meek, and try to hone your other skills. Life deals you a pretty face and a happy-go-lucky disposition? No sense becoming a shut-in — get out there and spend time with people; you'll probably find it very rewarding.

Specifically, the personality development mechanism needs to take four factors into account: its particular physical environment, its particular social environment, its particular body, and its particular cognitive traits. The latter includes things like intelligence, mental illness, natural temperament, etc. Some of these traits are shaped by the personality development process itself, but we start out with at least tentative versions of all of them.

SWOT analysis

I don't use the term strategy here loosely — it perfectly captures the role personality plays in our lives. Consider some of the things we mean by strategy:

- A strategy is a subset of behavior-space (just like a personality)

- A strategy is the dual of a niche (more on this in a minute)

- A strategy is driven by the unique features of a given domain (see here for an excellent discussion of 'strategy' vs. 'tactics')

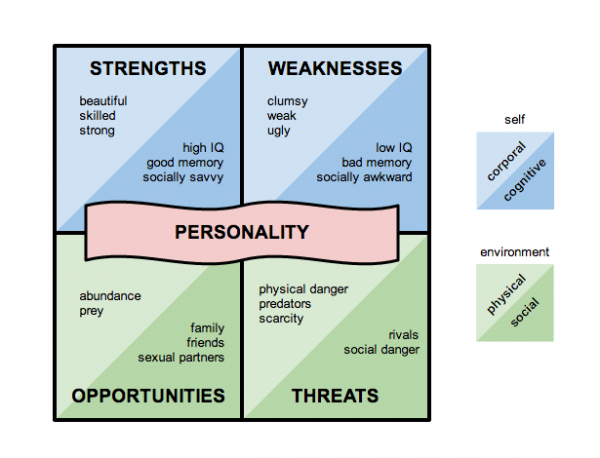

In business, one of the basic tools for strategic analysis is the SWOT matrix. SWOT stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. You can lay them out in a 2x2 — internal vs. external on one side, positive vs. negative on the other. Taken all together, the four SWOT elements provide the basic context and raw materials from which a strategic plan can be constructed.

We confront the same four elements in our personal and social lives. We have internal strengths and weaknesses (thanks to our bodies and inherited dispositions), and we face external opportunities and threats (in our physical and social environments). Taken together, these elements more or less determine the optimal strategy we should pursue.

Of course there's some room for creativity in this process, but the constraints are still hugely important. When life hands you lemons, you can make lemonade or lemon candy or lemon air freshener, but you can't make cherry pie.

So now that we understand personality's purpose (to make the best of what we're given), we can start to ask about how it develops. By what mechanism does the brain learn about itself and about its body? How does it know which behaviors to avoid and which to incorporate into its strategy?

(Hint: not by filling in a 2x2 on a whiteboard.)

The benefits of beauty

All else equal, it's good to be gorgeous. People treat you better. They listen attentively. They'll do favors for you before you even ask. And they let you get away with all sorts of things your uglier peers could never pull off.

Imagine for a moment that it's 1,000,000 BC, and you are a beautiful young Homo erectus. Q: How do you know you're beautiful?

A: You don't — at least not directly. Without language and without mirrors, all you can know is that people treat you well. They stare at you and seem to like being around you. Maybe they bring you gifts.

It's OK for you not to realize that you're beautiful. What matters is that people are responding to you in certain ways. And this is important because it informs the kind of strategy you'll need to develop for getting along and getting ahead in the world.

You'll find that you mostly get what you want thanks to your beauty. You'll be rewarded for projecting your physical presence, and for finding charming ways of flaunting and expressing it. Face-to-face interactions will usually work to your advantage, so you'll learn to seek them out, becoming more social than your uglier peers. You'll probably also find yourself rewarded for hinting at sexual favors, and as a result, you'll hone your flirting skills.

On the other hand, you'll find that (relative to your peers) you don't need to develop other skills in order to get what you want — skills like cunning or dexterity or physical strength. You might make a few stabs at using these other skills to get what you want, but your attempts will be clumsy and relatively less rewarding than using your physical charms, so you'll quickly abandon them in favor of doubling down on the beauty strategy.

And it's smart — maybe even optimal — for you to develop this way. You'll probably die before your beauty fades entirely, and given limited time and resources, you're better off focusing on what you're naturally rewarded for.

Reinforcement learning

What this illustrates is that you don't need an explicit (or even conscious) awareness of your strengths and weaknesses in order to develop a useful personality. All you need is good old-fashioned trial-and-error. Go out, probe the world (by interacting with it), and see what happens. If the outcomes are good, keep doing more of the same type of thing. If the outcomes are bad, stop and try something else.

I can't overemphasize how simple this is. It's little more than classic behavioral reinforcement, a la B. F. Skinner. "Look, a lever. What happens if I push it? Oh, some food! Maybe I should push it again. Yay, more food!" Push push push push push push push...

But the simplicity of the mechanism is also its strength. It's aggressively, single-mindedly focused on optimizing behavior to achieve good outcomes. Do more of what works, less of what doesn't — simple, but extremely powerful.

Q: if the mechanism is so simple, how do we get such complex and varied personalities? A: not from the learning mechanism itself, of course, but from the inputs that are fed into it — the different body types, early life histories, and basic cognitive tendencies, not to mention the endless variety of physical and social environments. The mechanism is dumb, but it's good at extracting information about the fit between person and environment, and incorporating that information into its "personality." Because there are many dimensions to the person/environment interaction, there are many dimensions to the resulting personality.

To be fair, the ease with which our brains manufacture concepts also plays an important role. We make sense of our experiences using a rich conceptual apparatus, and the richness of our inner mental lives gets reflected in our personalities. I'm not trying to deny that cognitive constructs play an important role — just pointing out that the learning mechanism is very simple and very general-purpose.

A model for personality development

Let's try to make this a little more formal. In a nutshell, this is what I'm proposing:

- Thanks to genes and early environment, we develop into a prototype — i.e., a child with a body and some basic tendencies. (Let's call this stage biological development.)

- Then, in the context of a specific physical and social environment, we become what we are rewarded for. (Let's call this stage socialization.)

For clarity we can think of these as distinct steps in a linear progression, but in reality they are ongoing processes that partially overlap and never fully terminate.

Notice how this cleaves 'nature' and 'nurture' at an oblique angle, rather than right down the middle. It's not a simple matter of nature providing raw materials and nurture shaping them into a unique personality. Rather, nature and nurture conspire (during biological development) to produce a prototype, and the prototype then negotiates with the environment (during socialization) to produce the final result.

And although the environment plays a pivotal role in socialization, it's misleading to call it 'nurture', since that word implies an intentional, helpful relationship (as of a mother toward her child). Instead, the relationship between child and environment is antagonistic. The child has to learn what he can get away with (vis-a-vis the environment) and in what ways he has to submit to it. That's why it's best understood as a negotiation.

I'll have more to say about this next time, when we'll look at personality using the toolkit of ecology.

Melting Asphalt

Melting Asphalt