Lately I've been thinking a lot about (what I'm going to call) swarms and hives — two different kinds of collective animal behavior.

Examples of swarms include: what gazelles do in herds, what fish do in schools, and what gnats do in those annoying mating balls every summer. Swarms lack central or global coordination; they're an every-creature-for-itself kind of affair.

Examples of hives include: what bees do around a beehive, what ants do around an anthill, and even (because I'm using "hive" in a very broad sense) what wolves do when they gather in packs. Hives, in contrast to swarms, are more globally-coordinated and manage to achieve at least a modicum of group-level agency.

As the most behaviorally-flexible species on the planet, humans are capable of both swarming and hiving. Human swarms include things like crowds, concert audiences, nightclubs, and gold rushes. Human hives include things like corporations, governments, armies, and orchestras — organizations with purpose.

Not everything falls cleanly in one camp or the other. A city, for example, is mostly just a swarm — an uncoordinated throng of individuals deciding to live near each other — but it simultaneously has a weak hivish overlay in the form of city government.

I'll have more to say about hives some other time. [Update: said it.] Today I want to talk about swarms.

Some swarms arise when there's a fixed resource to exploit — e.g., a gold rush or Black Friday sale. We might call these feeding frenzies. Other swarms arise because there are benefits to being around other people — e.g., a dance party. Economists call this kind of benefit a network effect.

In technical terms, a network effect occurs whenever each element of a network provides benefit to the other elements of the network.[1] In plain English, it just means the more the merrier.

Network effects take their name from the domain they were originally used to study, viz., physical networks like railways and phone lines. In a railway network, for example, it's easy to see how each additional station makes the entire network more valuable. (The more places I can travel on your network, the more likely I'll be to board one of your trains.) But "network" effects exist in all manner of places that don't immediately resemble a graph of connected elements. Herds of animals, for example, owe their existence to the network effect known as safety in numbers.

Swarms that rely on network effects can sometimes be hard to spot, in part because they often look like feeding frenzies. But most swarms are summoned and/or strengthened by network effects. In fact, a good rule of thumb is that the bigger the swarm, the more likely it's held together by a network effect.

Markets

Let's start with an easy case: the humble flea market. This is a swarm that's built almost entirely on network effects.

Consider a flea market with five vendors and ten customers. Each vendor is sad that there aren't enough customers, and each customer is sad that there aren't enough vendors. But each additional customer makes all the vendors happier, and each additional vendor makes all the customers happier. This is how flea markets grow to spectacular sizes.

You'll notice that towns rarely have two flea markets, at least not on the same day. This is because everyone's better off doing one big flea market instead of two smaller ones. That's the inexorable logic of network effects: smaller swarms end up glomming together into larger swarms.

Incidentally, this is what's been happening to the "Baby Bells" ever since the U.S. government broke up AT&T in the early 1980s: all the smaller telecom companies have been snapping back together into larger and larger conglomerates.

Of course, what's true of the flea market is true of most other market types, including shopping malls, financial markets, eBay, and all manner of mating markets around the world (and online).

Music

Why are popular songs popular?

The naive model is that a Top-40 song becomes popular simply because it's more appealing to more people. Everyone hears the song and (individually) decides that they like it, so they listen to it more often and it becomes popular. This would seem to be a pure feeding frenzy.

But remember our rule of thumb: wherever we see large swarms, we should expect to find network effects. And popular music swarms are huge. People have swarmed to the "Gangnam Style" music video over two billion times, for example — and who knows how many times they've seen or heard it in other media. This strongly suggests a network effect.

In order for a song to have a network effect, everyone who enjoys the song needs to benefit from each additional person who enjoys it. Which is kind of strange. If you already enjoy the song, why would you care whether I start to enjoy it?

One answer is that the more I like the song, the more I'm going to request it on the radio or decide to play it at one of my parties. My enjoyment of the song ensures that you'll get more opportunities to hear it. That's a network effect.

This effect is compounded by the fact that songs take time to grow on us — almost as if repetition were the key to music.

So this explains at least part of the network effect, but it's not entirely satisfying. For one, it doesn't explain why music needs to be repeated in order to grow on us. So here's another thought: maybe we like popular, often-repeated songs because they're better for singing and dancing.

If you're like most people, it's not nearly as fun to sing or dance by yourself. These activities are all about synchronizing with others, losing yourself in a crowd. But in order to sing along and dance with other people, everyone needs to be familiar with the song.

Say you're at a party. Which song would you rather hear next: some new song that no one's ever heard before, or the latest Taylor Swift? There's a reason "We Will Rock You" is played at sporting events and "YMCA" at every other wedding.

Even when people aren't singing or dancing, the popularity of a song is important for creating good vibes in large groups. Music is a quintessentially social behavior. We listen a lot on headphones now, but the beating heart of music still lies in the crowd. (In fact, synchronizing a crowd is probably why we evolved to do music in the first place.) If you play only obscure music at a backyard barbecue, your guests aren't going to enjoy themselves as much. And to the extent that people can enjoy a song on first listen, it's probably because there's a ton of repetition within a song: choruses, refrains, and of course the steady beat.

Repeat something often enough and publicly enough and it quickly becomes common knowledge. That's the key to music's popularity.

So what about concert-hall music? You can't sing along or dance to it — which maybe accounts for why it's not as popular today. And during its heyday, maybe it was popular because it was the only type of music that could be repeated widely enough and reliably enough for lots of people to become familiar with it. Sheet music was the original recording technology.

Brands

As I argued in an earlier essay, brands create network effects through advertising — in particular, by generating common knowledge. The more you believe that Budweiser is popular or that Chanel is a coveted brand (especially in the eyes of others), the more kudos you can anticipate for buying it and consuming it around others.

If you're picking a restaurant for out-of-town family, which one are you more likely to choose: Olive Garden (which has been advertising consistently on national TV), or that new restaurant that's been leaving flyers on your windshield? Faced with this kind of choice, empirically most people choose the better-known restaurant.

Like music, advertising relies on repetition — ideally in conspicuously public spaces — to induce common knowledge and thereby a network effect.

Political power

As I tweeted a few weeks ago: powerful people become powerful largely because they create network effects among their supporters.

Warlords, politicians, CEOs, celebrities, and cult leaders all exploit network effects.

When Genghis Khan is amassing his army, each additional troop benefits all the other troops — by making the army marginally more powerful.

When Hillary Clinton is amassing her coalition, she tries to build it in such a way that each additional supporter benefits all the others (or at least most of them). For a political coalition to be viable, supporters must get along with each other. That's how politics works at the systems level, but it's also true as a matter of psychology. If you support Hillary, and all you know about me is that I support her too, you're more likely to trust me. If you learn, however, that I don't share your politics, it's a recipe for distrust.

So: political power is largely a network effect. But here's the fun twist: you don't need an actual, live human being to maintain these network effects. Dead ancestors, gods, and other idols work the same magic.

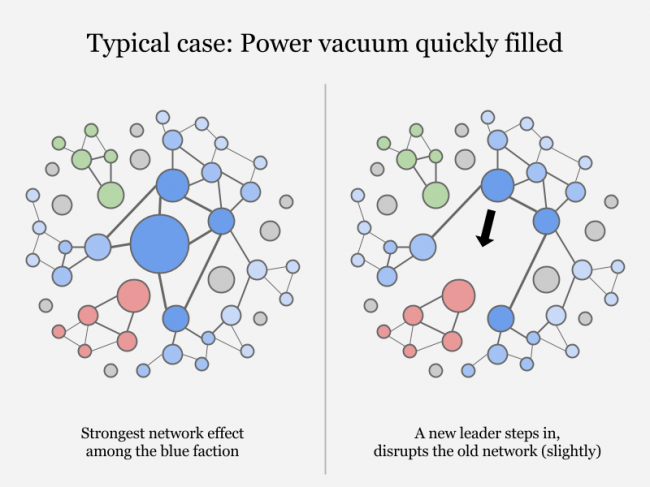

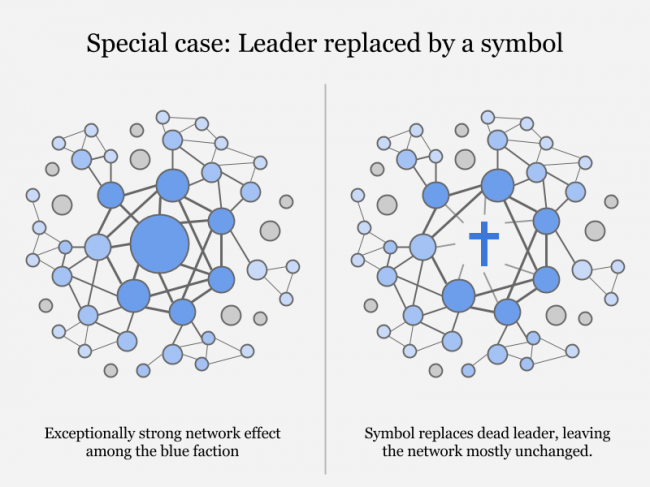

When an especially powerful leader dies, his network effect tends to linger even in his absence. It's held up by his network of supporters. In most cases the power vacuum gets filled pretty quickly, and a new regime (a new network effect) takes the place of the old one. But under certain conditions the leadership role can persist as a vacant niche, filled by a symbol in place of a living leader:

These network effects can persist long, long, long after a leader's death. In a very real sense, we're still held together by some of the network effects first summoned by Jesus, Mohammed, and (in America) the Founding Fathers. And to the extent that we exalt and worship these dead leaders, we show our allegiance to their still-living network effects.

Sermons and moral systems

Moral systems are some of the strongest network effects on the planet, right up there with cities, markets, and communication technologies.

A moral system is a set of norms bundled together with mechanisms for upholding them. These can get pretty complicated, but perhaps the simplest and most universal moral system is the Nice System:

- Norm: be nice to others.

- Enforcement: Punish those who aren't nice to others.

- (Bonus) Meta-norm: punish those who don't help enforce the norms.

Here's why it works. First of all, Nice people get along well with other Nice people, enjoying a strong network effect. Mean people, however, don't get along well with each other. Nor do Mean people get along with Nice people (as long as the Nice people are effectively enforcing their norms). When Mean people aren't punished for being Mean, however, they'll go on happily exploiting the community of Nice people, steadily undermining the network effect, i.e., the lynchpin of the whole thing.

(Note that in some circumstances, Mean people can develop their own moral system — an honor code among thieves. In this way they can achieve a small network effect. But because it's weaker than the network effect enjoyed by Nice people, the Mean Network won't be nearly as strong as the Nice Network. This is the advantage that Good has over Evil.)

When everyone's Nice to each other, they get along better, don't waste as much energy fighting with each other, etc. Each additional Nice member added to the Nice community makes the whole thing more valuable. Each Mean person, however, corrupts the network and must be kept out or otherwise at bay.

So Niceness sounds pretty great. Sign me up!

But wait — how do I know what Nice is? The norm just says, "Be nice to others." What does that mean, exactly?

This is where sermons come in. Sermons tell us what Nice is. Optionally, they also tell us: how to actually be Nice, how to spot Meanness in others, and what to do about it.

Without sermons, people won't be in agreement about what Nice means. If my idea of Nice and your idea of Nice are different, we won't get along as well. This degrades the network effect, which is strongest when everyone's on the same page.

Just as we've seen with songs and ads, sermons work by creating common knowledge through conspicuous public repetition.

Sermons needs to be public and conspicuous because everyone needs to know that everyone else has heard the same thing. By listening to a sermon along with others, everyone (tacitly) endorses its message and agrees to be bound by the moral system it's outlining.

Sermons need to be repeated because real human beings (unlike the hyper-rational archetypes contrived for use in logic puzzles) need to hear a sermon more than once in order to understand it, remember it, and infer all its consequences. Even when you understand a sermon after hearing it for the first time, other people might need more time and repetition. For a sermon to reach common knowledge — for it to fully saturate within the community — we need to ensure that even the slowest-witted others have internalized the message.

So the preacher gives weekly sermons at church, and because the virtues he's preaching have strong network effects, all the Nice people gather around — not just to listen, but to see and be seen. We might even say they flock to church.

Flock, swarm: same thing.

___

[1] To be maximally precise: network effects don't have to be beneficial. A new addition to a network can hurt all the existing items in the network, and that's still (technically) considered a network effect. But in practice, people only refer to network effects when they're beneficial.

Related thoughts and links:

- Robin Hanson on Mass Moralizing (OvercomingBias.com). Analyzes ads and other phenomena as sermons (very broadly construed).

- Elizabeth Margulis on why we love repetition in music (Aeon.co). Absolutely fascinating audio samples a few paragraphs in.

- The first multi-cellular organisms were born of a network effect; think of them as swarms that congealed.

- Other things I've written about network effects.

- Other things I've written about common knowledge.

Melting Asphalt

Melting Asphalt